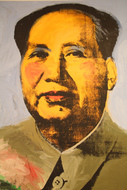

In college, I had the good fortune to take a seminar taught by a man who had lived an extremely interesting life. The seminar was on twentieth-century China, and the professor had witnessed it to a degree very few people could claim. His name is Sidney Rittenberg. For years, he was the only American citizen allowed into the inner circle of power in Communist China, spending 37 years there after World War II, 16 of which were spent imprisoned. His book, "The Man Who Stayed Behind" is one of my all-time favorites. As a 19 year old I couldn't appreciate the very large truths Professor Rittenberg related in his book. But as I grew older, they became more evident. He's told me that I'm not the only one who's told him they got more mileage out of his book after taking his class than during it. May 16 was the 50th anniversary of the start of the Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution, a counter-revolution that was called "China's Holocaust" by former president Li Xiannian. It ended only when its founder, Chairman Mao Zedong died in the fall of 1976. It was an attempt to make the Communist Party great again by purging it of elements he defined as antithetical to what the Party was - e.g., capitalism, tradition, bourgeois elements, art - anything that did not fit their ill-defined view. How did he do this? In part, by galvanizing the youth, to smash the old Communist Party he himself had forged, and recreate it in his own image. This was Mao's way of regaining supreme leadership after his widely derided failures during the earlier disaster of the Great Leap Forward. So he raised slogans to "Smash the Four Olds" (Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas). The world was divided into black and white: anything belonging to the "Four Olds" became the object of intense hatred and sanctioned violence. Mao succeeded perhaps past his own expectations. By raising slogans like "It is right to rebel!" or "No construction without destruction!" or "Revolution is not a dinner party!" he encouraged violence and class warfare. People's revolutionary spirit would be measured by the degree to which they would report on their fellow citizens. If someone was caught reading literature, that was something that should be reported. Artistic expression was frowned upon, and the so-called hong wei bing - Red Guards (Chinese Taliban?) would set upon buildings, furniture, items that were "merely" decorative, art pieces, styled hair, non-cadre clothing, to "cleanse" society to remove any trace of what they defined as the "Four Olds." Children denounced their parents, husbands their wives. Millions of people were persecuted, harassed, tortured, exiled, and killed. Professor Rittenberg himself went along with the Cultural Revolution. He gives an honest, first-hand account of what it was like, believing in a greater good. But he admits he misunderstood the point of the Cultural Revolution. The point was to create a revolution against the original Communist Party revolution - and debate, criticize, elect, discuss, and vote - but only within guidelines set by Chairman Mao himself. That oversight cost Professor Rittenberg 10 additional years in solitary confinement. He now sees Mao as a "brilliant, talented tyrant," responsible for the death and suffering of millions of people. You'd never know what he's been through: he has all the approachability of your own grandpa, except interspaced in his stories about olden times are truth bombs that leave craters in your mind. He was recently interviewed by Washington China Watch on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution (downloadable pdf here.) China has officially acknowledged that the Cultural Revolution was a mistake, but there has been relative silence in Chinese media on the occasion of its 50th anniversary. But the point should be obvious by now. The vitriol of our current election cycle bears more than a scant resemblance to the Cultural Revolution. I'm not saying they are the same - there are differences in both objective and execution. But the similarities are hard to ignore. A cult of personality around strongman candidates who can dish it out all day but can't take it back for a minute. Promises to solve massive social problems. The celebrity status of the leaders, who claim to represent the "proletariat" (working man) but have never belonged to the 99%. The raising of slogans hearkening back to a time of perceived purity. The narrative of foreign elements and classes tainting a "pure" society. Calls encouraging violence against these identified enemies by, say, offering to pay their legal bills. Activating a long-disregarded "underbelly" of society, empowering them, validating their simplistic worldview. "If you see something, say something." Ultimately, I think the Cultural Revolution was about control. I think Professor Rittenberg's takeaways from the Cultural Revolution - in which he participated in, and also was imprisoned for - are important takeaways for this election cycle as well. I can't say it better than him, so: The painful lesson here is that mistaken ideology can produce thoughtless cruelty in gentle, kind-hearted people...The most important lesson from the Cultural Revolution is to stay away from ideological blindness, from playing “follow the leader” wherever you are led, to think independently, critically, and not to believe in overnight miracles of social engineering.

2 Comments

Looking back over one's life it seems impossible to empirically prove that a certain experience was a "life-changing moment" - there are too many causes and too many effects. But we all instinctively "know" - without being able to prove it - that certain moments play a role in defining who we are.

A Facebook comment I read recently brought back such a 'teaching moment' from my past. The comment was written by a white woman who worked in retail in Tennessee, where there are not many minority groups. She wrote that she tried extra hard to smile and be helpful to women who wore hijab or who sported a bindi on their forehead, to try to make them feel as welcome as possible. And suddenly, I remembered my childhood. I spent the first decade of my life in Fayetteville, North Carolina - an achingly typical Southern town - in the 1980's. Fayetteville was (is?) an army town thanks to next-door Fort Bragg, one of the biggest US Army installations in the country. The Vietnam War was supported by many, and the town witnessed many marches and acts of civil disobedience during the Civil Rights movement, where segregation persisted. Even today, there is a sizeable Korean and Vietnamese population there, which I can only assume had to do with war brides. It's telling that the Market House, perhaps Fayetteville's best-known historic landmark, used to (on occasion) sell slaves. Needless to say, I was the only non-white person in my small kindergarten class. And I remember the awards ceremony for everyone at the end of the year in the gym. One of the awards was for perfect attendance. That year, three kids in the whole elementary school got the award. One was a young black girl whose name now escapes me. She was, as I recall, one of two or three black students in the entire school. The two white kids went up, one at a time, to receive their awards. After their names, there was polite applause. Then the black girl went up to get her certificate. No one clapped. No one, that is, except for my mother. The girl's parents, I suppose, were too stunned. I was five years old, but I remember. I asked my mother why no one clapped. I don't remember what she said (and neither does she), but how could she explain it to me at the time? I'd be remiss if I tried now to paint Fayetteville, North Carolina, or the entire South as a racist appendage to the United States. Yes, we did leave Fayetteville eventually, but most of the time, the worst we ever felt was the weight of being the funny brown family. I never got beat up or had slurs thrown at me. Unlike today - and with the possible exception of the Iran hostage affair - we were just a curiosity. Most folks were just curious - wanting to know more about who we were - without an identifiable trace of prejudice. Today, I'm still a proud Southerner who finds much about Southern culture worth celebrating. But there's no denying our dark history. That moment at the awards ceremony has come back to haunt me over and over again. I've tried to second-guess it - but my mother still remembers it. Racism exhibits itself in that split second pause - oh wait, she's black. I can't imagine every last person deliberately not clapping at the sight of a black girl achieving something - but the sentiment was clearly pervasive enough to cause an awkward silence that no one else felt comfortable breaking. And that just made it worse. I can't empirically prove it, but I think my becoming an immigration lawyer had something to do with that awards ceremony.  What's wrong with being called a 'moderate Muslim'? It has such a nice, calming ring to it; after all, moderate means not extreme. I should take it as a compliment that I'm being clearly distinguished from the terrorist gangs of the world. Except...don't. It's really rather annoying. First, 'moderate' is inherently a relative term. What's moderate to one is extreme to another - disagreement on what's moderate is frequent. It becomes merely a convenient label to say, "This is the level of religiosity I think is appropriate for you." Without guideposts to define what moderation is, the term is like a speed limit sign that says "Don't drive too fast." Second, the term is redundant. Qur'an 2:143 says: وَكَذَٲلِكَ جَعَلۡنَـٰكُمۡ أُمَّةً۬ وَسَطً۬ا And We have made you a moderate nation... The Arabic word وَسَطً۬ has three connotations: middle, moderate, and best. The concept of the middle being the best is something that transcends cultures and languages. China calls herself the "Middle Kingdom" - and the Chinese character for middle - 中 (zhong) - rather obviously depicts this. And in English "central" denotes "main" or "principal." The historian Ali ibn Atheer relates that virtue is sandwiched between vices. For example, courage lies between recklessness and cowardice, and generosity lies between prodigality and stinginess. The Islamic concept of "moderation" does not exist in a vacuum. It is defined as virtuous, and avoids extremes. A Muslim then, by definition, is moderate. This is how we understand and practice our faith. Anything that's not moderate is not Islamic. Terms like "Islamic terrorist" are misnomers: there is nothing Islamic about terrorism. Labels shape narratives. Professional Islamophobes like Frank Gaffney & Co. rely on the narrative of a clash of civilizations, tweeting ridiculous hashtags like #CivilizationJihad. To them, a terrorist waving the black flag presents the perfect picture of "real Islam" in practice. Yes, they call them extremists (because their actions are extreme by any standard) but in this framework, the 'moderate' ones are merely watered-down extremists. Give 'em a push, and any one of them could be activated into a real Muslim terrorist. Mere days after Gaffney was appointed foreign policy advisor for Ted Cruz, Cruz started spouting nonsense about patrolling Muslim neighborhoods - relegating the faith of 1.6 billion to not much more than a gang - as if merely being Muslim is an accurate precursor to terroristic behavior. No label is precise. They all have lexical limits, and it takes intellectual fortitude to remember this. I wrote once about three labels used by the anti-immigrant crowd: illegal alien, criminal alien, and anchor baby. Labels like these perpetuate the xenophobic narrative of immigrants as criminal, subhuman freeloaders, which makes them easy to exclude, malign, and hate. Take a few moments and think about a term before you use it. Turn it over in your mind. Is it accurate? Would it apply in other situations? Does the argument for or against the term require one to make a logical fallacy? |

AuthorHassan Ahmad, Esq. Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed