I've got "First World Privilege." People from war torn countries know it. No way I can know what it feels like to have a lifetime's work snatched away overnight. Or my home destroyed. Or my children lost. I've never had to just hold on to prayer or hope. There is always someone to call, a process, a service, an official, a friend. I find summertime Ramadan difficult with my A/C blasting. I can mostly say what I want. I've got the life people are thronging in the streets elsewhere to try to get a taste of. I am indignant about minor injustices - a harsher sentence for a defendant, a longer wait for a green card. I feel empowered and enormously satisfied when those injustices are corrected. Lazy, carefree self-absorbed youth, their noses buried in a phone? We should all be so lucky. People have been chased out of their homes since the beginning of time. But if it hasn't happened to you, you can't know what it feels like to miss your own life when it's taken away from you. Your life. So my closing thoughts on #WorldRefugeeDay: People who lose everything can either succumb to the depths of despair and be destroyed and forgotten, or burn with desire to rebuild and reclaim what was taken from them, and achieve greatness. An example of what a refugee can achieve with the right mindset? Exhibit 1: Moses. Exhibit 2: Jesus. Exhibit 3: Muhammad. (pbut) Their hardships made them great. They were maligned, ridiculed, tortured and banished. Yet today billions live by their example. They united people, connecting the haves with the have-nots, mandating compassion, and ensuring that displaced people were lent a hand, not given a boot. If you've got First World Privilege, what are you gonna do?

0 Comments

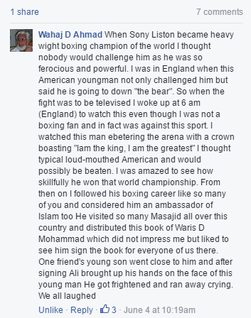

The Islamic funeral (janazah) of Muhammad Ali was thought-provoking for the American Muslim soul. He was a sportsman, a black man, an American, a rebel, a radical, a force to be reckoned with, a father, a husband, a brother - and a Muslim. I grew up after his heyday, but people from my parents' generation - immigrants - talked about waking up early to watch the inspiring fight, and how his zeal, ferocity, and skill won him admirers around the world.  When I was 10, I got to meet him when he came to Shaw University in Raleigh, NC. He took the time to play-box with us. Parkinson's had already started to slow him down - he could speak but in subdued tones. But I never forgot the humility and magnitude of a man who (in an era before such a photo would have been retweeted around the world in a nanosecond) would take the time to play with children as he completed an historic visit. That was just Ali. A champ. As a lawyer, I eventually read Clay v. United States, 403 US 698 (1971) and understood for the first time what this man gave up for his (at the time) highly unpopular principles. The words of Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) from the Qur'an came to mind: "O my Lord! Prison is more to my liking than that to which they invite me." [Qur'an 12:33] And that's exactly what Muhammad Ali publicly said: "Just take me to jail!" rather than fight in an unjust war. According to one account, the Supreme Court justices had initially voted to uphold his conviction, but were eventually swayed by the sincerity of Ali's beliefs. While the conviction was reversed on what might be termed a technicality, reversed it was all the same.

Next was the entirety of Surah 89, al-Fajr, "The Dawn." The last 4 verses are especially powerful at a janazah: But as for you, O tranquil soul, return to your Lord, pleased and accepted. Enter among My servants. Enter My Paradise." Of course, Ali is no longer suffering from a debilitating disease. But that's not why his soul is tranquil. A "tranquil soul" is one that has the supreme peace of mind that it did well in this life. It acted to please God, not the self, nor what the government decided was a patriotic duty. It didn't sell out, and it took a principled stand no matter the cost. It was humble enough to realize when it was wrong, and was never too proud or obstinate to change, evolve, grow, mature. It accepted the good and the bad, and never asked why me? It was tranquil. The third set of verses was from Surah 41, al-Fussilaat, or "The Details: "Surely, those who say: "Our Lord is God," and then go straight, the angels will descend upon them: "Do not fear, and do not grieve, but rejoice in the news of the Garden which you were promised. We are your allies in this life and in the Hereafter, wherein you will have whatever your souls desire, and you will have therein whatever you call for, as Hospitality from an All-Forgiving, Merciful One. And who is better in speech than someone who calls to God, and acts with integrity, and says, "I am of those who submit"? Good and evil are not equal. Repel evil with good, and the person who was your enemy becomes like an intimate friend. But none will attain it except those who persevere, and none will attain it except the very fortunate. We don't like blind faith. We are taught to question, to doubt, and to test hypotheses constantly. But there's something beautiful about belief that is pure, but not blind. It is what creates the strength to endure, to persevere. Would Ali have stood up to the US government if his convictions weren't rock solid? Should it matter that his convictions were religious in origin? Those beliefs told him not to fight, not to spread violence and mayhem, and to instead direct effort toward the real source of injustice. Islam requires a steadfast belief in God. And how does one act when they believe in God? Their integrity becomes their calling card. They repel evil with good, and turn their enemies into close friends. It's a tough road - but what about the Champ's life did not require perseverance? Many of us are very quick to shift our goalposts. Our principles are flexible, our ethics situational. In being taught to question everything, have we forgotten how to believe in anything? Have we become so progressive that we stopped progressing out of fear of not being progressive? Bertrand Russell famously said “the whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wise people so full of doubts." But what if the "fool" is certain that he must do good no matter the cost, whereas the wise person remains stuck in eternal preparation?

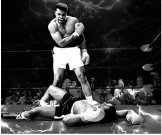

Muhammad Ali wasn't the kind of guy who got stuck overthinking. He was no scholar, but he believed in universal truths and he was strong enough to uphold them. Maybe it was that rigorous boxing training, not knowing how to stop at 99% that carried over outside the ring. Maybe it was all that self-confidence - checks he had the balance to cash. The strong black leaders of the 1960's - why does it seem so hard to find people today made out of the same stuff? I like to think we all have that inner strength if we weren't constantly told what to think and how to think it, or being told that belief in something good, without more, is worthless. I've always been proud of my faith as a "thinking" faith. One that invites debate and disagreement. It fit well with my liberal upbringing. But faith is, ultimately, a leap. Logic won't take you very far in matters of faith. But there is something to be said for strength of belief alone channeled into positive contribution. I feel a deeply satisfying reconciliation in the life and times of my brother in faith Muhammad Ali.  In college, I had the good fortune to take a seminar taught by a man who had lived an extremely interesting life. The seminar was on twentieth-century China, and the professor had witnessed it to a degree very few people could claim. His name is Sidney Rittenberg. For years, he was the only American citizen allowed into the inner circle of power in Communist China, spending 37 years there after World War II, 16 of which were spent imprisoned. His book, "The Man Who Stayed Behind" is one of my all-time favorites. As a 19 year old I couldn't appreciate the very large truths Professor Rittenberg related in his book. But as I grew older, they became more evident. He's told me that I'm not the only one who's told him they got more mileage out of his book after taking his class than during it. May 16 was the 50th anniversary of the start of the Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution, a counter-revolution that was called "China's Holocaust" by former president Li Xiannian. It ended only when its founder, Chairman Mao Zedong died in the fall of 1976. It was an attempt to make the Communist Party great again by purging it of elements he defined as antithetical to what the Party was - e.g., capitalism, tradition, bourgeois elements, art - anything that did not fit their ill-defined view. How did he do this? In part, by galvanizing the youth, to smash the old Communist Party he himself had forged, and recreate it in his own image. This was Mao's way of regaining supreme leadership after his widely derided failures during the earlier disaster of the Great Leap Forward. So he raised slogans to "Smash the Four Olds" (Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas). The world was divided into black and white: anything belonging to the "Four Olds" became the object of intense hatred and sanctioned violence. Mao succeeded perhaps past his own expectations. By raising slogans like "It is right to rebel!" or "No construction without destruction!" or "Revolution is not a dinner party!" he encouraged violence and class warfare. People's revolutionary spirit would be measured by the degree to which they would report on their fellow citizens. If someone was caught reading literature, that was something that should be reported. Artistic expression was frowned upon, and the so-called hong wei bing - Red Guards (Chinese Taliban?) would set upon buildings, furniture, items that were "merely" decorative, art pieces, styled hair, non-cadre clothing, to "cleanse" society to remove any trace of what they defined as the "Four Olds." Children denounced their parents, husbands their wives. Millions of people were persecuted, harassed, tortured, exiled, and killed. Professor Rittenberg himself went along with the Cultural Revolution. He gives an honest, first-hand account of what it was like, believing in a greater good. But he admits he misunderstood the point of the Cultural Revolution. The point was to create a revolution against the original Communist Party revolution - and debate, criticize, elect, discuss, and vote - but only within guidelines set by Chairman Mao himself. That oversight cost Professor Rittenberg 10 additional years in solitary confinement. He now sees Mao as a "brilliant, talented tyrant," responsible for the death and suffering of millions of people. You'd never know what he's been through: he has all the approachability of your own grandpa, except interspaced in his stories about olden times are truth bombs that leave craters in your mind. He was recently interviewed by Washington China Watch on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution (downloadable pdf here.) China has officially acknowledged that the Cultural Revolution was a mistake, but there has been relative silence in Chinese media on the occasion of its 50th anniversary. But the point should be obvious by now. The vitriol of our current election cycle bears more than a scant resemblance to the Cultural Revolution. I'm not saying they are the same - there are differences in both objective and execution. But the similarities are hard to ignore. A cult of personality around strongman candidates who can dish it out all day but can't take it back for a minute. Promises to solve massive social problems. The celebrity status of the leaders, who claim to represent the "proletariat" (working man) but have never belonged to the 99%. The raising of slogans hearkening back to a time of perceived purity. The narrative of foreign elements and classes tainting a "pure" society. Calls encouraging violence against these identified enemies by, say, offering to pay their legal bills. Activating a long-disregarded "underbelly" of society, empowering them, validating their simplistic worldview. "If you see something, say something." Ultimately, I think the Cultural Revolution was about control. I think Professor Rittenberg's takeaways from the Cultural Revolution - in which he participated in, and also was imprisoned for - are important takeaways for this election cycle as well. I can't say it better than him, so: The painful lesson here is that mistaken ideology can produce thoughtless cruelty in gentle, kind-hearted people...The most important lesson from the Cultural Revolution is to stay away from ideological blindness, from playing “follow the leader” wherever you are led, to think independently, critically, and not to believe in overnight miracles of social engineering. Looking back over one's life it seems impossible to empirically prove that a certain experience was a "life-changing moment" - there are too many causes and too many effects. But we all instinctively "know" - without being able to prove it - that certain moments play a role in defining who we are.

A Facebook comment I read recently brought back such a 'teaching moment' from my past. The comment was written by a white woman who worked in retail in Tennessee, where there are not many minority groups. She wrote that she tried extra hard to smile and be helpful to women who wore hijab or who sported a bindi on their forehead, to try to make them feel as welcome as possible. And suddenly, I remembered my childhood. I spent the first decade of my life in Fayetteville, North Carolina - an achingly typical Southern town - in the 1980's. Fayetteville was (is?) an army town thanks to next-door Fort Bragg, one of the biggest US Army installations in the country. The Vietnam War was supported by many, and the town witnessed many marches and acts of civil disobedience during the Civil Rights movement, where segregation persisted. Even today, there is a sizeable Korean and Vietnamese population there, which I can only assume had to do with war brides. It's telling that the Market House, perhaps Fayetteville's best-known historic landmark, used to (on occasion) sell slaves. Needless to say, I was the only non-white person in my small kindergarten class. And I remember the awards ceremony for everyone at the end of the year in the gym. One of the awards was for perfect attendance. That year, three kids in the whole elementary school got the award. One was a young black girl whose name now escapes me. She was, as I recall, one of two or three black students in the entire school. The two white kids went up, one at a time, to receive their awards. After their names, there was polite applause. Then the black girl went up to get her certificate. No one clapped. No one, that is, except for my mother. The girl's parents, I suppose, were too stunned. I was five years old, but I remember. I asked my mother why no one clapped. I don't remember what she said (and neither does she), but how could she explain it to me at the time? I'd be remiss if I tried now to paint Fayetteville, North Carolina, or the entire South as a racist appendage to the United States. Yes, we did leave Fayetteville eventually, but most of the time, the worst we ever felt was the weight of being the funny brown family. I never got beat up or had slurs thrown at me. Unlike today - and with the possible exception of the Iran hostage affair - we were just a curiosity. Most folks were just curious - wanting to know more about who we were - without an identifiable trace of prejudice. Today, I'm still a proud Southerner who finds much about Southern culture worth celebrating. But there's no denying our dark history. That moment at the awards ceremony has come back to haunt me over and over again. I've tried to second-guess it - but my mother still remembers it. Racism exhibits itself in that split second pause - oh wait, she's black. I can't imagine every last person deliberately not clapping at the sight of a black girl achieving something - but the sentiment was clearly pervasive enough to cause an awkward silence that no one else felt comfortable breaking. And that just made it worse. I can't empirically prove it, but I think my becoming an immigration lawyer had something to do with that awards ceremony.  What's wrong with being called a 'moderate Muslim'? It has such a nice, calming ring to it; after all, moderate means not extreme. I should take it as a compliment that I'm being clearly distinguished from the terrorist gangs of the world. Except...don't. It's really rather annoying. First, 'moderate' is inherently a relative term. What's moderate to one is extreme to another - disagreement on what's moderate is frequent. It becomes merely a convenient label to say, "This is the level of religiosity I think is appropriate for you." Without guideposts to define what moderation is, the term is like a speed limit sign that says "Don't drive too fast." Second, the term is redundant. Qur'an 2:143 says: وَكَذَٲلِكَ جَعَلۡنَـٰكُمۡ أُمَّةً۬ وَسَطً۬ا And We have made you a moderate nation... The Arabic word وَسَطً۬ has three connotations: middle, moderate, and best. The concept of the middle being the best is something that transcends cultures and languages. China calls herself the "Middle Kingdom" - and the Chinese character for middle - 中 (zhong) - rather obviously depicts this. And in English "central" denotes "main" or "principal." The historian Ali ibn Atheer relates that virtue is sandwiched between vices. For example, courage lies between recklessness and cowardice, and generosity lies between prodigality and stinginess. The Islamic concept of "moderation" does not exist in a vacuum. It is defined as virtuous, and avoids extremes. A Muslim then, by definition, is moderate. This is how we understand and practice our faith. Anything that's not moderate is not Islamic. Terms like "Islamic terrorist" are misnomers: there is nothing Islamic about terrorism. Labels shape narratives. Professional Islamophobes like Frank Gaffney & Co. rely on the narrative of a clash of civilizations, tweeting ridiculous hashtags like #CivilizationJihad. To them, a terrorist waving the black flag presents the perfect picture of "real Islam" in practice. Yes, they call them extremists (because their actions are extreme by any standard) but in this framework, the 'moderate' ones are merely watered-down extremists. Give 'em a push, and any one of them could be activated into a real Muslim terrorist. Mere days after Gaffney was appointed foreign policy advisor for Ted Cruz, Cruz started spouting nonsense about patrolling Muslim neighborhoods - relegating the faith of 1.6 billion to not much more than a gang - as if merely being Muslim is an accurate precursor to terroristic behavior. No label is precise. They all have lexical limits, and it takes intellectual fortitude to remember this. I wrote once about three labels used by the anti-immigrant crowd: illegal alien, criminal alien, and anchor baby. Labels like these perpetuate the xenophobic narrative of immigrants as criminal, subhuman freeloaders, which makes them easy to exclude, malign, and hate. Take a few moments and think about a term before you use it. Turn it over in your mind. Is it accurate? Would it apply in other situations? Does the argument for or against the term require one to make a logical fallacy?

Like my colleagues at the immigration bar, I hear a lot of depressing stories. It's a defense mechanism, I suppose, to not empathize after you've heard dozens, if not hundreds, of such stories. But sometimes, as one of my colleagues put it, there's a fleeting moment when you feel some facsimile of the horror your client felt, and it puts it into perspective. Lawyers obviously have to be objective - but we can't lose our humanity in the process. The trick is to use that empathy as fuel for constructing a winning argument.

This happened to me recently on two asylum cases from Syria. |

AuthorHassan Ahmad, Esq. Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed